Sign Up

To Keep In Touch

Receive the latest news, program updates, and event announcements from the Richard Hampton Jenrette Foundation.

Author: Grant Quertermous, CAHPT Curator & Director of Collections

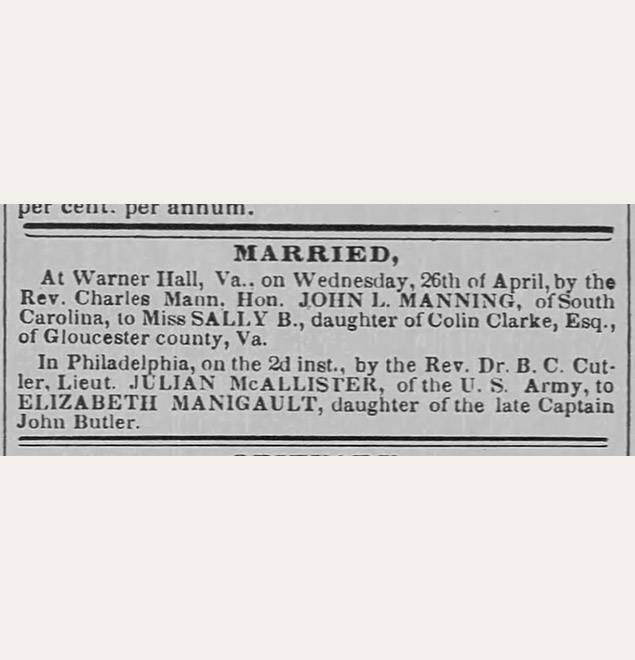

“Married, At Warner Hall, Va., on Wednesday, 26th April, by the Rev. Charles Mann, Hon. John L. Manning of South Carolina, to Miss Sally B., daughter of Colin Clarke, Esq. of Gloucester County, Va.” The Charleston Mercury, May 8, 1848

Photograph of Sally Bland Clarke Manning, ca. 1849. Classical American Homes Preservation Trust, 2018.474

Upon her marriage to John Laurence Manning in April of 1848, nineteen-year-old Sally Bland Clarke Manning became the mistress of Millford. A native of Gloucester County, Virginia, Sally left her home and family and moved more than four hundred miles south to Millford, arriving in May of 1848. Her impressions of the house, which had been constructed, decorated, and furnished by her husband and his late wife, heiress Susan Hampton Manning, survive in a series of letters written to her mother and sister in the Virginia Tidewater. The letters also provide an interesting insight into Sally’s adjustment into her roles as stepmother to Manning’s three young children, and manager of a large and complex household and of her reception by the large network of her husband’s extended family who lived near Millford. Within six years of their 1848 marriage, Sally’s husband was elected Governor of South Carolina, and she would find herself married to one of the most powerful politicians in the Palmetto State.

Sally Clarke was just eighteen years old when she met thirty-one-year-old John Laurence Manning when both were vacationing at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia (now West Virginia), in September of 1847. Manning was a familiar figure at the Springs where he and his Hampton relatives owned cottages and sought refuge from the heat of the South Carolina summers as well as the company of fellow members of the antebellum southern planter aristocracy. Sally and her family may have gone to the springs for the health benefits prescribed by doctors of the era—fresh mountain air and the regular consumption of the mineral-rich spring water. Or perhaps it was the numerous social activities including balls, parties, and horse races the resorts offered that drew her family to them. Sally’s parents might have hoped the visit to White Sulphur Springs would also allow their daughter to meet several eligible bachelors including one that would result in a suitable match. What they hadn’t anticipated was John L. Manning.

Spring House at The Greenbrier, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. HABS Photo. Library of Congress.

Manning would have been considered an ideal match in the eyes of numerous parents looking to marry off their eligible daughters that season at the Springs. Wealthy through the ownership of his Louisiana sugar plantations, the master of Millford was also Princeton educated (though he would complete his final year of studies at South Carolina College after the 1836 death of his father), and a bit of a dandy as indicated by surviving portraits and extant receipts for his clothing purchases. John S. Skinner, a newspaper reporter who encountered Manning at White Sulphur Springs that year, described him as “Manning of S.C.,…a large sugar planter in Louisiana, and who, judging from his physiognomy, and his physique, ought to be in the lead of a legion of horse…” Civil War-era diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut once confided to her diary that Manning was “the handsomest man in the world.”

Widowed three years earlier when his wife, Susan, died from complications of childbirth on October 31, 1845, Manning was also a rising star in South Carolina state politics. The son, nephew, and great-nephew of former South Carolina governors, he was serving his second year in South Carolina’s state senate in 1847, after having already served four years in the state’s house of representatives.

Sally Bland Clarke was the second daughter and one of the seven surviving children of Colin and Mary Goode Lyle Clarke of Gloucester County, Virginia. The Clark family resided at Warner Hall Plantation, relocating from Chesterfield County, Virginia in 1834. Warner Hall was previously owned by several generations of the Lewis Family who had constructed the mid-18th century house on the property, but the estate had its origins as a mid-17th century head grant of 6,000 acres given to Augustine Warner, the great-grandfather of George Washington.

Colin Clarke, Sally’s father, was born in Powhatan County, Virginia, at his father’s plantation, Keswick, and graduated from the College of William & Mary. He later represented Powhatan County, and then Chesterfield County, in the Virginia House of Delegates. Sally was born in either Chesterfield County, Virginia, or in the city of Richmond. Her parents were living in the Madison Ward of Richmond when the U.S. Federal Census was taken in 1830. She is likely the 1 “female under 5 years of age” enumerated within the household. Through her mother, Sally was a direct descendant of Virginia patriot and Continental Congressman Richard Bland, a likely reason for her middle name.

Warner Hall in the early 20th century. Image courtesy of Warner Hall Inn.com

Whatever the circumstances of John and Sally’s meeting, subsequent letters indicate that they shared an equally mutual attraction. The week after Sally and her family departed the Springs to return to Gloucester County, John L. Manning and other mutual acquaintances formed during the visit journeyed to Sweet Springs, another resort in the region. It was not uncommon for travelers to make a circuit of the numerous resorts in the mountains of Western Virginia including White Sulphur Springs, Hot Springs, Warm Springs, Yellow Sulphur Springs, and Sweet Springs. From Sweet Springs, a mutual acquaintance, Susan Caroline Wardlaw of Abbeville, South Carolina, wrote to Sally on September 14 noting, “the pleasure of writing you would have been delayed a little longer, but for our Col. M[anning] who wished me to write now.” Miss Wardlaw went on to note that Manning “is very sad & only truly consoles himself in talking of you and such sweet things as he says! I am sure you would like to hear. He told me once when he looked very grave out of those eyes, that he would give half his crop to see you then.” The writer notes that Manning himself planned to depart the Sweet Springs the following day. “We all miss you very much and I do particularly,” Warlaw continued, “but Mr. Manning makes up for all, in that way. I assure you he has lost his appetite & looks like a person in search of something. No doubt he has written all these things, and many more, much sweeter, but I know you will not object to hearing them twice.” Wardlaw admitted her own attraction to the wealthy politician and planter in the letter but acknowledged that he was blind to any woman except Sally.

While Sally and her family returned to Warner Hall, John L. Manning traveled west to Kentucky, visiting Louisville and Lexington. He even visited Ashland and dined with its owner, former Secretary of State Henry Clay, while he was in Lexington. He then headed south to Nashville, Tennessee, and from there traveled by riverboat down the Cumberland, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers, to Louisiana and his plantations. Manning was clearly thinking about Sally as he wrote to her frequently throughout the trip, describing his feelings for her and wondering why she had not yet written. By October, Manning was already contemplating a proposal of marriage to Sally. He asked his traveling companion and relative Thomson T. Player, widower of his late wife’s sister, Mary Sumter Hampton Player, to write their former mother-in-law, Mary Cantey Hampton, in order to seek her approval. “It would be a blight upon his feelings if he did not hope for your kind approval of his marriage,” Player wrote to Mrs. Hampton.

Envelope and Letters written by Sally Bland Clarke to John L. Manning. Williams-Chesnut-Manning Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina.

By mid-November 1847, Manning wrote to Sally, “should your parents receive me as fondly as I hope they will, I hope that you will not think of a protracted engagement. I object to them as useless & frequently productive of much evil.” He then requested that she not deem him “overweeningly vain in proposing my marriage before you have told me that you love me.”

Part of Sally’s delay in writing him back may have been due to the acknowledgement by her parents of their age difference. Mr. and Mrs. Clarke recognized that their nineteen-year-old daughter’s suitor was twelve years older and a widower who already had three small children. This initially led them to caution their daughter about the match, out of fear that she would end up being a “glorified governess” to Manning’s three young children. However, he won them over, and they soon warmed to him. Mrs. Clarke, Sally’s mother, urged her daughter to remember that her happiness was “their primary concern,” not Manning’s wealth or social standing. “So my dear Sallie, if [Manning] is the prize your Sister, Mrs. Gordon, and every body else thinks him, we consider you the greater of the two,” Mrs. Clarke wrote to her daughter.

By December, Manning was planning another trip to Virginia, during which he would ostensibly propose marriage. He wrote to Sally’s brother-in-law, Douglas H. Gordon, at Warner Hall asking “your assistance, first to become assured and secondly to be married at an early period.” Gordon was married to Sally’s older sister, Mary Ellen, so his assurance to Mr. and Mrs. Clarke that Manning was a suitable match for their younger daughter would be especially important.

Inaccurate reports that Manning and Sally’s marriage had already occurred reached Charleston before he even returned from his Virginia travels. In a letter to Sally written on February 28, 1848, the day he stepped off the boat in Charleston, he noted that “by some means or other the whole city /and I know almost everyone in the city/was under the belief that I was married and would scarcely believe my assertion to the contrary.” After a few days in Columbia, Manning headed west to Louisiana where, he noted in a letter to Sally, he would see his children for the first time in more than six months. They had traveled there to Houmas with their uncle and aunt Preston several months earlier as he was returning to South Carolina from his own Louisiana travels. In a subsequent letter, Sally asked him to give them each a kiss from her, already accepting her role as their stepmother.

What Manning didn’t elaborate on in his correspondence with Sally was his efforts to purchase outright the Louisiana plantations that he had received upon his 1838 marriage to Susan Hampton. At the time of Susan’s death in 1845, her children inherited the plantation property as her heirs in accordance with Louisiana’s legal code, not him as her spouse. As the children were still minors when Susan died, Manning acted as a guardian in managing the plantations until he succeeded in purchasing them outright.

The marriage announcement of John L. Manning and Sally B. Clarke. The Charleston Mercury, May 8, 1848 via Newspapers.com

Just twelve days before their wedding, Manning wrote to Sally from New Orleans, where he had travelled after visiting his plantations in Ascension Parish. The letter also indicates his pet name for his future bride, as he opens the letter, “My darling Sal.” “In three hours, I will be on my way to Mobile, and in six or seven days I hope to reach Millford to make some little arrangements there for the reception of its future mistress,” he wrote, “I have had the premises put into something like order, & have thoughts of many little things which I supposed would be agreeable to you.” He goes on to write, “Ah! My love! How very happy I am to think that in a few days you will be my joyous and blooming bride. How many tender emotions follow the thought! How fair & beautiful does the future seem to me, when with you by my side all nature will seem to smile upon us, as if rejoicing in eternal happiness.”

After the announcement of their engagement, Sally received a letter from her future mother-in-law, Elizabeth Peyre Richardson Manning, widow of former South Carolina Governor and United States Congressman Richard Irvine Manning, Sr. “I know you of course only through the representation of my son to whom you are shortly to be united for life, but from those representations you will receive from myself and the rest of his connexion here, a warn and affectionate welcome. We have but little to offer you upon your arrival to your new home, beyond this, but I shall feel happy if I can be in any wise instrumental in assisting my son to make you feel that in leaving all the endearments of your own home, you will meet with new connections who will be second only to your parents in their effort to enable you to pass through life without pain or regret.”

Wedding Chalice; Ball, Tompkins & Black, ca. 1848. Classical American Homes Preservation Trust, 2013.011

As the newspaper notice reported, John and Sally were married at Warner Hall on April 26, 1848. The ceremony was officiated by Rev. Charles Mann, the Episcopal rector of Ware Parish Church of Gloucester. To commemorate the occasion, Sally’s mother presented her son-in-law with a silver chalice, made by New York silversmiths Ball, Tompkins, and Black and engraved “JLM from MGC.” Following the wedding, John L. Manning took Sally to Millford. She detailed the trip in a lengthy letter written to her mother, describing everything from “the ordeal” of her wedding night to her reception by Manning’s large extended family. After traveling south by train from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Wilmington, North Carolina, they boarded a boat bound for Charleston. “I had a wretched uncomfortable time,” she wrote, “dreadfully seasick all the time, but I set it now as one of the bright spots in my short married life for there it was that my dear husband shone forth in all his glory. It would have done your heart good, dearest Mother, to have seen his tender anxious care of me he never left me for a moment nursed me as though I had been an infant and soothed me so gently.” After arriving in Charleston, they boarded a carriage for the journey to Millford, arriving in the evening to see it by moonlight.

“As to Millford I could not begin to describe it now. We drove up to the door by moonlight and I pronounce it the most beautiful imposing place I ever saw,” she recounted. “We had not been in the house many minutes when [Manning’s] Mother came over and after meeting in the most affectionate manner calling me her daughter she insisted our thus going to her house and said we must spend the first night under her roof.” So the newlyweds got back into their carriage and journeyed the short distance to Mrs. Manning’s house, “where the rest of the family were. They were all equally affectionate calling me Sister & Cousin & Aunt. Little Dot [Manning’s niece] calls me ‘Sally Clarke.’” The next morning, Sally and John went back to Millford so she could really see the house and grounds. She described her impression of the house at length in that same letter to her mother:

“Millford far surpassed my expectations in every respect. The house is like an old Baronial hall, beautifully finished and furnished in every respect …The furniture is all elegant but not fine, no carved roses about it but plain and substantial. The parlors are beautiful – The hall…is enormously large with sofas and chairs of leather on either side and tables with marble tops on which are placed old busts which were dug from the earth in Italy. The house is beautifully situated. It looks like an old place that had been settled for a century. You enter by a large iron gate, near which, on a little elevation, is a beautiful porter’s lodge, and drive, by a winding avenue up the hill to the house. The piazza is of mosaic marble with large Corinthian pillars sprung up to the roof. Near the fish pond is [a] beautiful Gothic springhouse built over a spring of delicious water. I have not had time to go over all the grounds yet for I have been in company all the time.”

Entrance Hall at Millford, ca. 1900. CAHPT Archives.

At 19 years old, Sally Bland Clarke Manning was now the mistress of Millford, a house that was lavishly furnished with silvered door hardware and mirrors ordered from New York City, marble mantels acquired from Philadelphia, and furniture commissioned from the shop of noted cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe & Son of New York. Manning had spared no expense when constructing the house ten years earlier, installing the latest technology, including a furnace system with floor grates to supply warmed air and a water ram allowing water from a nearby spring to be piped into the dependencies. Sally’s description of Millford from her 1848 letter provides the earliest documented description found to date of the furnishings and décor within the house.

One can only imagine how overwhelming the whole experience must have been for someone of her age who had previously lived a relatively sheltered life on a rural Virginia plantation. Sally also met her stepchildren. She noted in one letter to her mother that five-year-old Mary was seated beside her playing with a box that held sealing wafers. Mary, along with her brothers, Richard (9 years old), known by the family as “Dickie,” and Wade Hampton Manning (3 years old), were largely left in the care of their maternal grandmother, Mary Cantey Hampton, following their mother’s sudden death in 1845. The 1850 U.S. Federal Census indicates that all three of Manning’s children were residing with Mrs. Hampton in Columbia. Sally also wrote to her mother about meeting Mrs. Hampton and her surviving daughter, Caroline Hampton Preston. While Sally’s initial letter doesn’t survive, Mrs. Clarke’s reply does, in which she wrote, “So rejoiced do I feel that your interview with them, and their relations is over, and blessed with such a happy result.”

Sally’s surviving letters do not reveal her thoughts about living in a house where the presence of the first Mrs. John L. Manning was still felt. At least two portraits of Susan Hampton Manning were displayed at Millford, and she likely played a role in the selection of much of the lavish décor found throughout the house. At one point Manning contemplated selling Millford, perhaps because he also felt the house represented his collaboration with Susan. Their nephew Wade Hampton III wrote to him, indicating his interest in purchasing the property and recalling that Manning had mentioned a desire to sell it. That transaction never came to fruition, and Manning kept Millford. However, Sally would eventually get a house in which she would oversee the decoration and furnishings herself. In the mid-1850s, Manning constructed a house on his Louisiana plantation, and Sally, with the aid of a cousin, furnished and decorated it to her own tastes.

Benjamin Pleasant and Ann Johnson. Carte-de-Visite photograph, ca. 1860. Williams-Chesnut-Manning Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina.

At the time of her marriage, several enslaved individuals accompanied Sally from Virginia to Millford, perhaps as part of a dowry. Later 19th century census records from Sumter County indicate that these individuals, including Benjamin Pleasant (ca. 1826-1910) and Ann Morris Johnson (ca. 1839-1919), who remained at Millford following their Emancipation, were both born in Virginia. Ben Pleasant became John L. Manning’s enslaved valet who traveled extensively with him (as far as Canada) and later served as a caretaker on the Millford property until his 1910 death. In one 1856 letter, Sally mentions to her husband that Ben’s sister Matilda was for sale but raised concerns against purchasing her for Millford, although she ultimately noted that she “would like to see Ben gratified.” In another 1861 letter, Sally asks her husband to “ask Ben if he can buy some scraps from the shoemaker of sole leather & upper leather” in order to mend their son’s shoes. Johnson was a Lady’s Maid to Sally and later served as nurse to the Manning children. She continued to reside at Millford following Emancipation and died on the property in 1919.

Just five months after their 1848 marriage, Sally’s older sister, Mary Ellen Clarke Gordon, died in Virginia from a complication of childbirth. Then the following year, the mansion house at Warner Hall was destroyed by fire. Sally’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Clarke, continued to reside on the property and expanded a dependency building rather than reconstructing the mid-18th century mansion house, which was not rebuilt until the 20th century.

Sally would eventually have four children with John Laurence Manning, three of whom would survive infancy. Their first, a son whom they named John Laurence Manning Jr., was born in 1849 but died less than a year later in 1850. Another son, Douglas Gordon Manning, nicknamed “Guppy” in childhood, was born in 1851. He succumbed to Typhus in 1870, dying before his twentieth birthday. A daughter, Ellen Clarke Manning, a namesake for Sally’s deceased sister, was born in April 1857 and lived well into the 20th century. Another son, Colin Clarke Manning, a namesake for Sally’s father, was born after the Civil War in 1867.

Carte de Visite of John L. Manning. Classical American Homes Preservation Trust, 2022.06

John Laurence Manning was elected the 65th Governor of South Carolina in 1854. During his two-year term, he and Sally resided in Columbia at the Lorick-Baker House, located on Hampton Street. Manning was also starting to make his name in national Democratic politics. Following the completion of his term as Governor, he declined an offer by President James Buchanan to serve as Minister to Russia. In 1860-61, the couple sat for portraits by artist George Peter Alexander Healy. Manning wrote to his wife from Charleston on March 31, 1861, noting, “Healy has been exhibiting his paintings and many seem to think that the likeness of yourself & that of me excellent, but that mine is defective.”

Initially against Succession, Manning eventually switched his position and served as a delegate to South Carolina’s Succession Convention, the wealthiest in attendance. His source of wealth was profits from sugar grown on his Louisiana plantations where he enslaved more than 600 individuals. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he served as Colonel and Aide-de-camp on the staff of Confederate General P.T.G. Beauregard. He was, as diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut described in her diary, “pleased as a boy to be on Beauregard’s staff.” After the Battle of Manassas, Manning returned to his seat in the South Carolina state senate, later downplaying his Confederate military service in his 1865 amnesty application to President Andrew Johnson.

Sally, like many Southern wives, did her part to support the Confederate war effort as well as oversee the daily operation of Millford while her husband was away, first at the convention and later in his military service. Sally’s letters written during the early months of the Civil War, while John L. Manning was away from Millford, provide an interesting insight into this era of the property’s history. Sally also corresponded regularly with her stepson Dicky (Richard I. Manning), who was serving in Hampton’s Legion, and with her family in Virginia. In one letter Colin Clarke, Sally’s father, describes the Confederate artillery placed on nearby Gloucester Point, saying that “Gloucester point never looked so since Tarleton evacuated in Oct [17]81.” He and her mother reported hearing the artillery barrage from Warner Hall. Four of Sally’s brothers also saw action during the war. Her brother Maxwell was an officer in the Confederate Navy, while Colin Jr. was a Major in the Confederate Quartermasters Department, but died at Warner Hall in 1862. Brother Powhatan “Powie” Clarke was a cavalry officer and later Chief of Ordinance for the District of Western Louisiana, and John Clarke, Sally’s youngest brother, was a soldier in the 30th Virginia Infantry.

While her husband was away from Millford, Sally and her children stayed at neighboring Homesley, the plantation of her brother-in-law, Richard I. Manning, Jr. He also served as a Colonel in the Confederate Army until his sudden death from pneumonia in October, 1861. Sally’s letters suggest that she and her two children, Elizabeth and her two children, as well as other members of the extended Manning-Richardson were all residing at Homesley and that they had, per one letter, a “full house.”

Sally Bland Manning by G.P.A. Healy, 1860. Private Collection

G.P.A. Healy’s 1860 portrait of Sally Bland Manning echoes an 1865 description provided by Dr. Charles Briggs, a Union Army surgeon with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, who visited Millford with General Edward Potter a few days after the end of the war: “Mrs. Manning carried on her arm the basket of keys characteristic of the southern housekeeper. She is a tall pale imperious looking lady and wore flowing black robes. Her attitude and manner of addressing the General was quite dramatic after the style of a Roman matron, expressing confidence in the southern cause and a readiness to suffer all hardships.”

“I had quite a long conversation with her,” Dr. Briggs noted in his letter, “She evaded skillfully the points I raised. She said that a planter’s life was not so luxurious as some people supposed. She spoke if the necessary daily supervision of everything and care of the sick – duties that perhaps some fashionable women neglected as they might similar ones at the north, but the ladies with whom she associated did not neglect them. I called her attention to the procession of the contrabands wh[ich] could be seen from the portico, and asked her if it did not look like the passage to the Red Sea. It was enough to live for to see that sight.”

Sally and John Laurence Manning, ca. 1880.

Gravestones of John Laurence Manning and Sally Bland Manning located in the Manning family plot at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, Columbia, South Carolina.

Sally Bland Manning died after contracting pneumonia at Millford on December 31, 1884. Her widowed mother, Mary Goode Lyle Clarke, also living at Millford, died the previous day. Sally was buried at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Columbia, in the Manning family plot, adjacent to the two sons who predeceased her as well as her husband’s parents and siblings. John L. Manning would only survive Sally by five years, dying at the home of his youngest daughter in Camden, South Carolina, in October 1889. He was buried by Sally’s side in the churchyard at Trinity.

Throughout their 45-year marriage, the stream of letters written back and forth between them provide a valuable insight into the daily activities at Millford as well as important details that would be otherwise lost to history, including the names and tasks undertaken by those enslaved on the property. Dr. Briggs’ 1865 description of Sally as a “Roman matron” suggests that in the intervening years since her marriage, she had become fully comfortable in her role as mistress of Millford and wife to one of the most politically prominent and powerful men in South Carolina. His description also suggests that she was someone unafraid to offer a rebuttal in a civil discourse with a Union officer.

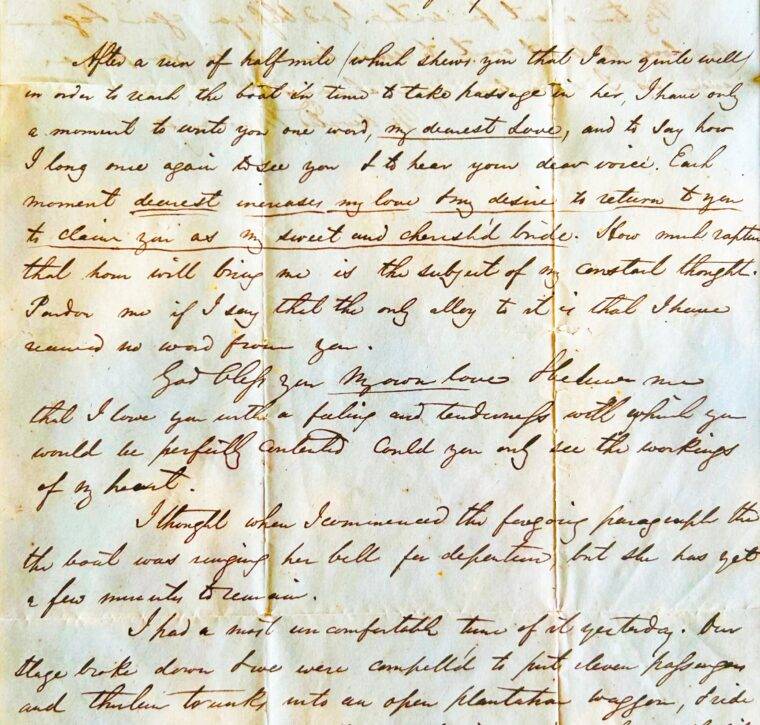

John L. Manning to Sally Bland Clarke, March 11, 1848. CAHPT, 2014.112

The extant letters between Sally and John L. Manning also indicate the couple’s mutual affection that was deepened by a lengthy marriage and the births of their children. The correspondence reveals that Manning viewed Sally as a trusted partner, advisor, and confidant, filling his letters with professions of his love for her and the happiness she had brought to his life and that of their children.

Article Categories: Site History